Stories To Tell Books BLOG

Filtering by Category: Planning Your Book’s Contents

Planning Your Family History Book: What’s Your Style?

Biff Barnes

Plan Your Family History Book Sooner Rather Than Later

Biff Barnes

What Are Good Journals?

Biff Barnes

Memoir or Autobiography: Which One's for You?

Biff Barnes

Bring an Ancestor to Life with a Biographical Sketch

Nan Barnes

A Chasm for Family History Writers

Biff Barnes

Interactive Timeline Takeaway

Nan Barnes

We were in the Bay Area this past weekend and stopped in to Oakland’s excellent museum to see how the California history exhibit has been faring in our absence. I love museums, not just for their collections, but for the art of exhibiting information itself. Reading books is nice, but even I am willing to concede that interactive learning beats all.

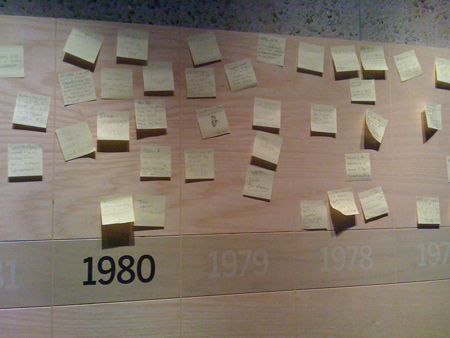

Here’s one interactive exhibit I thought was a great idea for family historians. The timeline spans a long wall, so many people can view it and post on it at the same time. Imagine their conversations as they make their choices for the most important events of the year.

Here’s one interactive exhibit I thought was a great idea for family historians. The timeline spans a long wall, so many people can view it and post on it at the same time. Imagine their conversations as they make their choices for the most important events of the year.

I can see many applications for this exercise, which could be set up temporarily and inexpensively at a family reunion, a seminar, or a book planning session. And it’s adaptable: just change the timeline to decades, for a longer-in-scope book, or to months or even weeks, for a memoir spanning a shorter period.

The key, I think, is the post-it notes. (What a brilliant invention – how did we ever live without them?) We recently suggested using index cards to get organized in one of our seminars, but some folks just couldn’t envision the color-coding. Anyone can get organized with post-its.

Lessons from a Self Publishing Author's Experience

Biff Barnes

“[I spent] six years sailing around the world. Three years writing about it,” says Larry Jacobson.

The result was a book, The Boy Behind the Gate, which Jacobson recently self published. He discussed his experiences in a recent post on The Book Designer Blog titled 8 Keys to Self Publishing Success. Jacobson’s book was intended for commercial distribution, but his observations are interesting for authors planning both commercial distribution and limited non-commercial distribution to family and friends.

The first, and in some respects most daunting, challenge he faced was planning and organizing the project. “Fortunately for me, I had been and continued keeping my ship’s logs and personal logs. I also had hundreds of emails back and forth with friends and family,” said Jacobson. “All of this documentation left with me nearly 2,000 pages to work from, and I was truly overwhelmed.” Developing a sound outline involved making decisions about the book’s intended audience, goals, illustrations, and format.

Once he had a draft of his manuscript, Jacobson had to make some critical decisions about how much help he would need to bring it to publication. The first regarded editing the draft. Jacobson said, “I have always enjoyed writing but knew I had limitations. Be smart enough to know what you don’t know. I hired a professional editor and we worked together for almost two years on three very intense edits/revises/re-writes.”

With a fully edited manuscript in hand Jacobson again decided he needed help, this time from a book designer. “I know how to use Word on the computer and I have iPhoto, so why couldn’t I just do the design and layout myself? (Laugh Out Loud),” he said. “Not a chance-I tried a couple of pages-and knew I needed a professional.”

Finally Jacobson explored his publishing options and decided on self publishing. “While I do know that publishers supposedly have the distribution down, in a world where distribution of books is no longer set in its ways,” he reasoned, “I decided to go alone and start my own publishing company. I didn’t have the time or patience to deal with a publishing house…even if they were interested.”

The lessons from Jacobson’s experience for anyone considering self publishing are clear. First, take the time to develop a clear plan for the book which will allow you to write a good draft. Second, decide where you need professional help in preparing the manuscript for publication. Finally, consider the options concerning the publisher or printer who can best meet your goals for the book.

Click here to read Larry Jacobson’s post.

Dealing With the Dark Side of Family History

Biff Barnes

Is there a black sheep in your family? A seldom (never?) talked about scandal?

If so, you are probably asking yourself, “How much truth should I tell in writing my memoir or family history?”

There’s been a lot of discussion in recent genealogy blogs about rattling the skeletons in your family’s genealogical closet. Almost every family’s story has had its traumatic moments and dark secrets. They may feel uncomfortable or difficult to talk about. Do you have to include them in your memoir or family history? No. Should you?

One way to make decisions is to imagine the people who will read your book. Would you be comfortable revealing the information to them face to face? Is that what you want? If not, just don’t include it.

Consider these questions before revealing painful truths:

- Is this truth necessary to tell your larger story?

- Will the story hurt anyone if you bring it out in the open?

- Was it common knowledge at the time it happened?

- Does it deliberately vilify someone? Does your telling the story show malice or spite?

- Is it fair to all concerned?

- Are you telling the story only for its sensational value?

- Are people in the story still alive? Can you talk to them about it?

- How will it affect any children involved?

- What will be gained if you include it?

- What will be lost if you omit it from your story?

Ernest Hemmingway, in the preface to his memoir, A Moveable Feast, offers us a good guideline. He wrote, “For reasons sufficient to the author, many places, people, observations and impressions have been left out of this book.”

What's the Difference Between a Chronicler and a Historian?

Biff Barnes

What’s the difference between a historian and a chronicler or documentarian? Anyone contemplating writing a family history ought to give the question some thought. A person who wants to chronicle events is primarily concerned with creating and documenting a record of everything that happened. It’s not surprising that the daily newspaper I read is called The Chronicle. It sees its responsibility as capturing events great and small which occurred the previous day. Some are of earthshaking import, but most are not. There’s a reason that newspapers often wind up on the bottom of people’s birdcages.

A genealogist’s research is intended to create to create that sort of documented record of his ancestors. It involves gathering facts and demonstrating through documentary evidence the accuracy of those facts.

But, when a genealogist decides to become a family historian by turning his research into a book his role changes. You need to recognize that you are writing for an audience and that you have a responsibility to present your family’s history in the most interesting way possible to that audience.

- Rule One: Realize that just because you have gone to great length to acquire knowledge about a particular detail or event and to document its factual basis it won’t necessarily be interesting or important in the eyes of your audience.

Your readers will probably find it more interesting and significant that your ancestor landed on Utah Beach on D-Day than that he spent eight weeks in training at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina. The two facts don’t deserve equal time in your book just because they both happened. One might not even need to be there at all.

- Rule 2: Recognize that life’s turning points, triumphs and epiphanies aren’t distributed equally over the years of a person’s life. Look for the dramatic and significant events in your ancestor’s life. If there were stretches of years when things just rolled along without anything of interest happening, you don’t have to give those years equal time (or maybe even any time) in your book.

Getting away from straight chronology is a good way to free yourself to focus only on the big events giving the most attention to the most important aspects of your family’s history.

A historian interprets events. She makes choices about what is important among the many facts at her disposal and uses them to show why some events are especially significant. By choosing anecdotes that are interesting and unusual to tell your ancestors’ story you will also make that story engaging for your audience.

Tried and True Organization for Your Family History?

Nan Barnes

What’s the best way to organize a big project, like a family history book?

We regularly teach a seminar, How to Plan and Organize a Family History Book. We recommend that people begin with the big ideas first, listing what should go into the book. And ultimately, they should arrive at an outline. But in the middle between these two points, there’s a murky area, a process that seems to stump our audiences.

Ironically, the sticking point comes when we refer to a process we all probably learned in middle school: index cards. Remember them? There are software variations now, using the same principles of organization.

We like index cards because they are hands on, they’re visual, and they are easy to change, add or discard. You can use different colored cards to designate big ideas, subheadings and specific details. After you develop one organization, it’s easy to move the cards to a different arrangement of ideas. When you’re happy with the way the cards are arranged, you can transfer the ideas on the index cards to paper and you’ve got a preliminary outline.

For most folks the index card method makes perfect sense, but others just don’t get it. “Should it be a red card or a green card?” they ask. “How many subheadings should I have under a big idea?” The very strength of the system, its flexibility, confuses people.

Do you have other techniques to suggest? How do you like to organize ideas for a big project? Post a comment and share with us, and our readers, your favorite method of organizing. We’ll look forward to reading what you have to say and I’m sure our readers will too.

What Do Readers Want?

Biff Barnes

Would you like to know how to make your book more appealing to readers? Would it help the revision and editing process if you knew which sections of the book readers found most interesting and which they skipped over?

Tools to answer questions like these may soon be available on Scribd, a social publishing website sometimes called the You Tube for documents. Visitors can browse millions of documents or “upload your PDF, Word, and Power Point docs to share with the world’s largest community of readers.”

Scribd CEO Trip Adler recently announced that the site would offer a free tool, Scribd Stats. The new statistics will provide, he said, “new data on reading that’s never been available before."

Jason Kincaid of Tech Crunch described some of types of data available with the new package including:

- Data on search queries that led people to your document

- Data on what people are searching for within your document

- Graphs that allow you to track your document’s popularity over time

- Data analyzing Scribd’s Read Cast feature which let’s readers share content they’ve just read on Facebook or Twitter

“Perhaps the most interesting feature of the new Scribd Stats package is the heat maps that will run down the side of each document…,” said E.B. Boyd of Fast Company. [see image above] “The heat map represents the entire document. Red indicates pages that users spent the most amount of time on, blue the least. Clicking on a section of the heat map takes you to that particular page in the document.”

Ann Westpheling, Scribd’s new strategic partnership manager who recently joined the company after 11 years in publishing marketing, said…“If I create an excerpt with material from three romantic novels, I can now see which author drove the most traffic. Experimentation [with different marketing strategies] becomes more meaningful.”

The implications of the new data are potentially enormous.

Boyd said, ”The stats could provide insight into how long people read different kinds of material--leading, perhaps, to new optimal lengths for different genres of books--as well as how reading speeds vary by day of the week or by age of reader--which could also lead to changes in how authors write.”

Click here to read Jason Kincaid’s Tech Crunch article.

Click here to read E.B. Boyd’s Fast Company article.

Click here to visite the Scribd website.

Organizing a Family History - BYU Ancestors

Biff Barnes

If you’ve been following our recent posts (or even if you haven’t) we have been looking at how to organize a family history book. The Brigham Young University TV series Ancestors offers some good insights on the subject. The website for the series which first aired in 1997 addresses several questions you’ll want to think about as you decide how to organize your book.

- What type of history do you want to create?

- How many people or generations should you include?

- Who is your intended audience?

- What style will you use? This section focuses on decisions about chronological or topical organization or combinations of the two. It also offers video clips which explain some of the choices you will face in organizing your family history.

- Do you need an index or source citations?

The website offers a variety of resources for family historians. It’s worth a look.

Click here to visit the BYU Ancestors site.

Topical Organization for a Family History

Biff Barnes

Best-selling author Bill Bryson (Mother Tongue, Made in America: A Short History of Nearly Everything) has written a new book that might be of interest to people planning a family history.

The New York Times recently reviewed Bryson’s newly published At Home: A Short History of Private Life. Says reviewer Dominique Brown, “Bryson’s focus is domestic; he intends, as he puts it, to ‘write a history of the world without leaving home.’” The book is organized around the rooms of Bryson’s house. “Moving from room to room, talking while we walk…” he touches on such disparate topics as antique parlor chairs, buttons, vitamins, stairs as a cause of fatal accidents, the Erie Canal, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, the history of ice, Building materials, the numerous words important into English when India dominated the cotton trade, pillows, petroleum, and guano as fertilizer.

“Bryson’s conceit is nifty, providing what business majors might recognize as a “loose-tight” management structure,” said Brown, ”flexible enough to maintain a global scope without losing track of the mundane.”

It’s that organizational structure that can be useful for a family historian looking for an alternative to lock-step chronology. Whether frustrated by a shortage of stories to supplement the genealogical facts about some ancestors or simply looking for a more interesting way to relate the family history, topical organization can be a useful tool.

A book might be organized around

- Life experiences such as occupations, education, child raising, military service, migrations (everything from the stories of immigration to America to moves across the country or across the street) or food.

- Values like courage, intelligence, sense of humor, creativity, persistence, hard work

- Character traits including courage, intelligence, sense of humor, creativity, persistence, hard work

Whichever topics around which you decide to organize your family history you will be able to add interest by using the historical context of the time and place in which ancestors lived to supplement their stories.

Click here to read the full review of At Home: A Short History of Private Life.

Interesting Examples of Topical Memoirs About Food

Biff Barnes

“I am a foodie; I always have been, and I’m not ashamed to admit it,” says Fliss on her blog All Lit Up as she opens a post titled Food For Thought: Three Food Memoirs. That was enough to get me – a fellow foodie - to read it. But the post contains some lessons for memoir and family history writers as well.

One of the most perplexing problems encountered by many people who want to write a memoir or family history is how to organize their books. The might do well to look at the three books Fliss reviews.

Cooking for Mr. Latte by Amanda Hesser

The book covers a period between when Hesser, a food writer, meets her future husband and their wedding day. The chapters were originally written as articles and each is followed by a series of recipes.

French Milk by Lucy Kinsley

This, says Fliss, is “a graphic novelesque travelogue of a monthlong vacation in Paris,” during which “Knisley is almost totally obsessed with food.”

Lunch in Paris by Elizabeth Bard

This memoir covers the first few years of Bard’s life after she moves to Paris. It is well-seasoned with recipes.

Each of the three books is an example of a writer successfully creating an interesting book by limiting the scope of their stories both chronologically and thematically. By organizing their books around a single topic the writers assured a unity of purpose and coherence.

These books are examples of an organizational technique that will work for both memoir and family history and for a multitude of topics.

Click here to read Fliss’ reviews.

What's Your Book's Theme?

Nan Barnes

One of the most common obstacles faced by family historians is how to organize the mountain of research they have accumulated. The first advice they are likely to be given is to decide on the scope of their book. Should they choose a single line in their ancestry and trace its story. Or would it be better to start with a specific ancestor and look at all of that person’s descendants.

Once the decision about scope is made a second question arises. What common underlying experiences or ideas, relationships or connections run through the lives of the ancestors you will write about? In short, what is the theme that ties together your family’s history? Beyond the unique aspects of that experience how have the events experienced by the people you describe been part of the universal human experience?

Here are some examples of themes in different kinds of family stories:

- Wisdom, values or lessons and passed from generation to generation: That was the case for books written by both major presidential candidates in the last election. Barrack Obama in Dreams From My Father and John McCain in Faith of My Fathers.

- Racial, ethnic or cultural identity: It’s an experience Booker T. Washington captured in his autobiography Up From Slavery where he observed “my race must continue passing through the severe American crucible.” Frank McCourt was able to turn his Irish-American experience into a Pulitzer Prize winner with Angela’s Ashes. But you can give that experience an interesting twist as Jane Ziegelman did in 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement in which she uses the ethnic foods of the Germans, Irish, Italians and East European Jews on New York’s Lower East Side to tell their immigrant stories.

- The migration west: Jane Applegate’s Snookum: An Oregon Pioneer Family’s History and Lore is an excellent example of documenting the experience of settling the frontier.

- Family occupation or career: British novelist Robert Louis Stevenson used it to tell his family’s story in Records of a Family of Engineers. The book, recently published after work by the Gutenberg Project, explores the family firm that built most of Scotland’s lighthouses.

- Political persecution: Kati Marton’s Enemies of the People: My Family’s Journey to America tells the story of her parents, both Hungarian journalists who were imprisoned by the communist government after World War II and finally escaped to the United States after the failure of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

In thinking about the theme for your book look for both what’s unique about the experiences of your ancestors and what universal lessons those experiences might teach your readers.